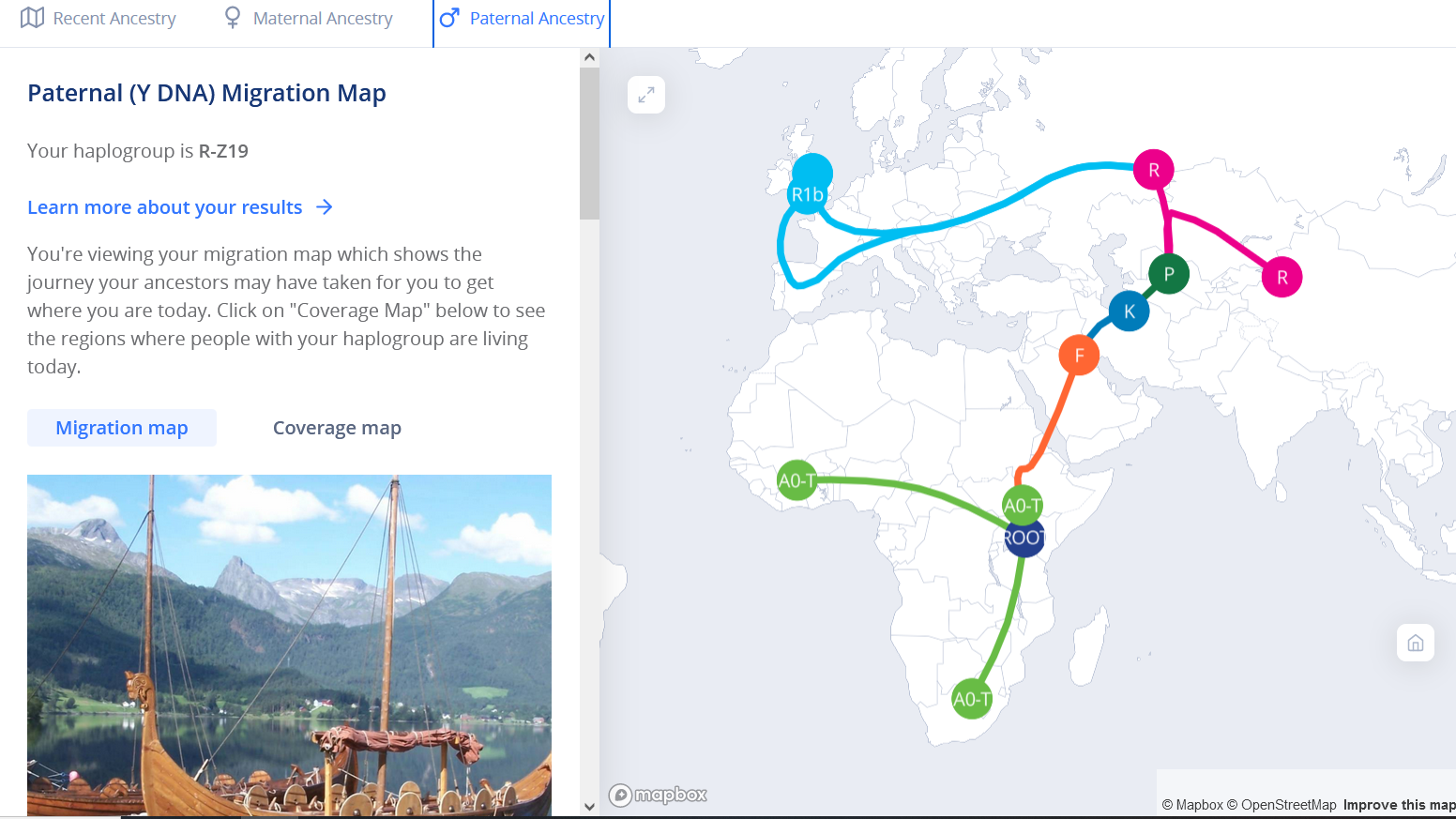

Stadig ny informasjon kommer om mitt opphav. —-Skal vi tro det er jeg i slekt med Vikingene som dro i Østerled slik Svenske vikinger gjorde.—–Ikke utenkelig når en ser på min fars- og morslinje som deler seg i dette området.—(Se bildene nederst på siden)— -Altså har jeg opphavelig slektninger i Ukraina,Hviterussland også kalt Belarus, Russland osv.—Det var disse vikingene som kom fra Scandinavia som ble kalt «RUS» og ga navn til Russland.——.

MEN——-Vikingtiden var bare 2-300 hundre år fra ca. år 800……Mine aner er lenge før det og viser tilbake til KELTERNE.–https://snl.no/keltere

Så har slekten kommet til Scandinavia før eller under Vikingtiden. —-Og senere i Vikingtiden blitt med Svenske vikinger i Østerled.——

Hvis du vil ha en fornøyelig lesestund om Vikingtiden kan sterkt anbefales boken om Vikinghøvdingen

» Røde Orm» og hans reiser i vest- og østerled.

Introduction

The image of the Vikings that most of us have grown up with – the image in popular culture – is that of a tall, bearded, blond man on a longboat. Probably wearing a style of horned helmet, he’s a battle-hardened warrior heading out on a raiding mission to kill in and to steal from coastal towns or monasteries in the rest of Europe.

In truth, the stories of these terrifying Norsemen (men from the North) are mostly told by their survivors, as in their early years there was no written record kept by Scandinavian people themselves (Brink & Price 2008, Jesch 2015). This means that – until recently – we had to rely on the writings of people from outside of Scandinavia, people who might have had a vested interest in portraying Vikings in a negative light, and later on writings from towards the end of the Viking age after the introduction of Christianity into Scandinavia. These were written by people who – again – might have had an interest in showing the civilising effects of their new, more modern, ways (Brink & Price 2008, Jesch 2015).

While all Vikings were Norsemen, not all Norsemen were Vikings. These raiders were in fact only a subgroup of the Norse population; they all they desired the opportunities and wealth that foreign lands could offer, whether through conquest or through trade and settlements for better farming and fishing.

The Viking era lasted lasted from 789 AD to approximately 1066 AD (Brink and Price 2008, Jesch 2015) and had an enduring impact upon the peoples of Europe. Many of the royal families of Europe can trace their lineage back to the Viking rulers and the kingdoms that they founded across the continent.

Now, using the latest academic and scientific research, we are able to tell you how similar your DNA is to those ancient Norsemen that have captured imaginations for generations.

Understanding your Results

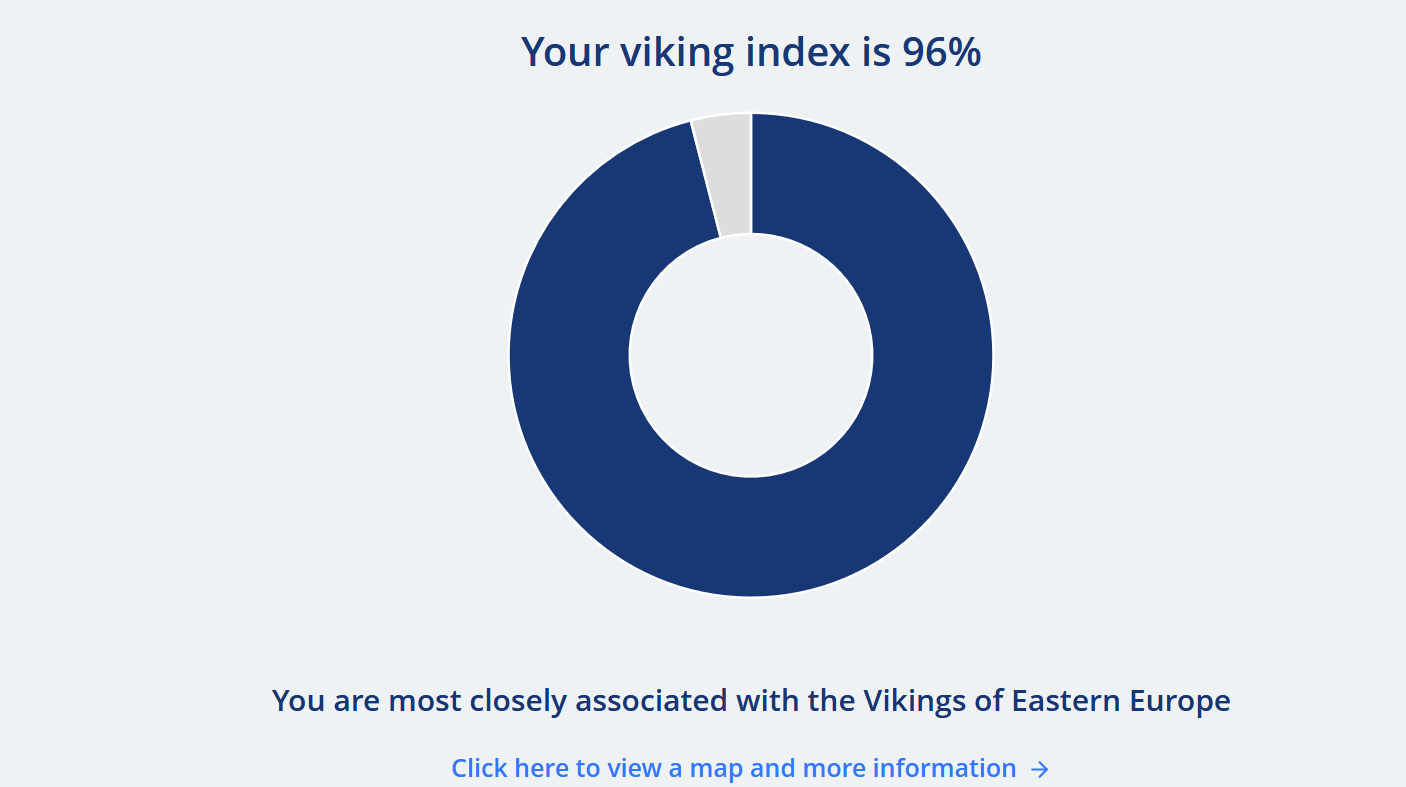

Viking Index

The Viking index represents the amount of DNA that you share with ancient Vikings. First, the genetic similarities between your DNA and the DNA obtained from ancient viking and non-viking samples are computed. This allows us to estimate how much DNA you share with each group. In order to then interpret and contextualise this calculation we compare your value to that of all other Living DNA users. This yields your Viking Index score. The Viking Index score allows you to see where your result falls in comparison to the whole range of Viking Indexes across the Living DNA user base. For example, if your Viking Index is 80%, this means that your DNA is more similar to Viking DNA than 80% of all Living DNA customers.

The Viking Population Match

The Viking Population match indicates which Viking population your DNA is most similar to. We have identified 4 distinct Viking populations from our the analysis of ancient DNA. These are Norwegian Vikings, Swedish and Danish Vikings, British and North Atlantic Vikings, and Eastern European Vikings. We compare your DNA data to genetic models describing the genetic similarity and variability of these populations in order to identify your closest match.

Ancient Viking DNA

A total of 446 Viking samples were used for our analysis. Ancient human remains from the Viking Age were excavated in a diverse set of 80 archaeological sites within the current borders of the United Kingdom (including mainland Great Britain and the Orkney Islands), Ireland, Iceland, Denmark (mainland, the Faroe Islands and Greenland), Norway, Sweden, Estonia, Ukraine, Poland and Russia.

Samples were excavated in the major areas of Viking influence and have been dated to between the late 8th and late 11th centuries CE. Human remains were excavated from burial sites. Most regions that were once inhabited by Vikings saw a gradual increase in the use of inhumation burials (opposite to cremation burials) during the Viking Age as a result of the adoption of Christian burial practices in Scandinavia and the Baltic Sea area from the 10th century onwards. This implies that there is a limited bioarchaeological record of human remains from the Early Viking Age, whereas it is much richer for the latter stages of the Viking Age. It must be taken into account that the record of individuals given an archaeologically visible burial is highly skewed towards social elites, who maintained wider networks and enjoyed higher degrees of mobility than the average person – this is relevant when assessing population mobility and diversity.

Ancient human remains (mostly teeth or petrous bones) were processed and DNA was extracted and sequenced in order to be used to generate our Viking Index and Viking Population Match results. The Viking genetic data was retrieved from three scientific publications Margaryan et al., 2020, Krzewińska et al., 2018, Ebenesersdóttir et al., 2018.

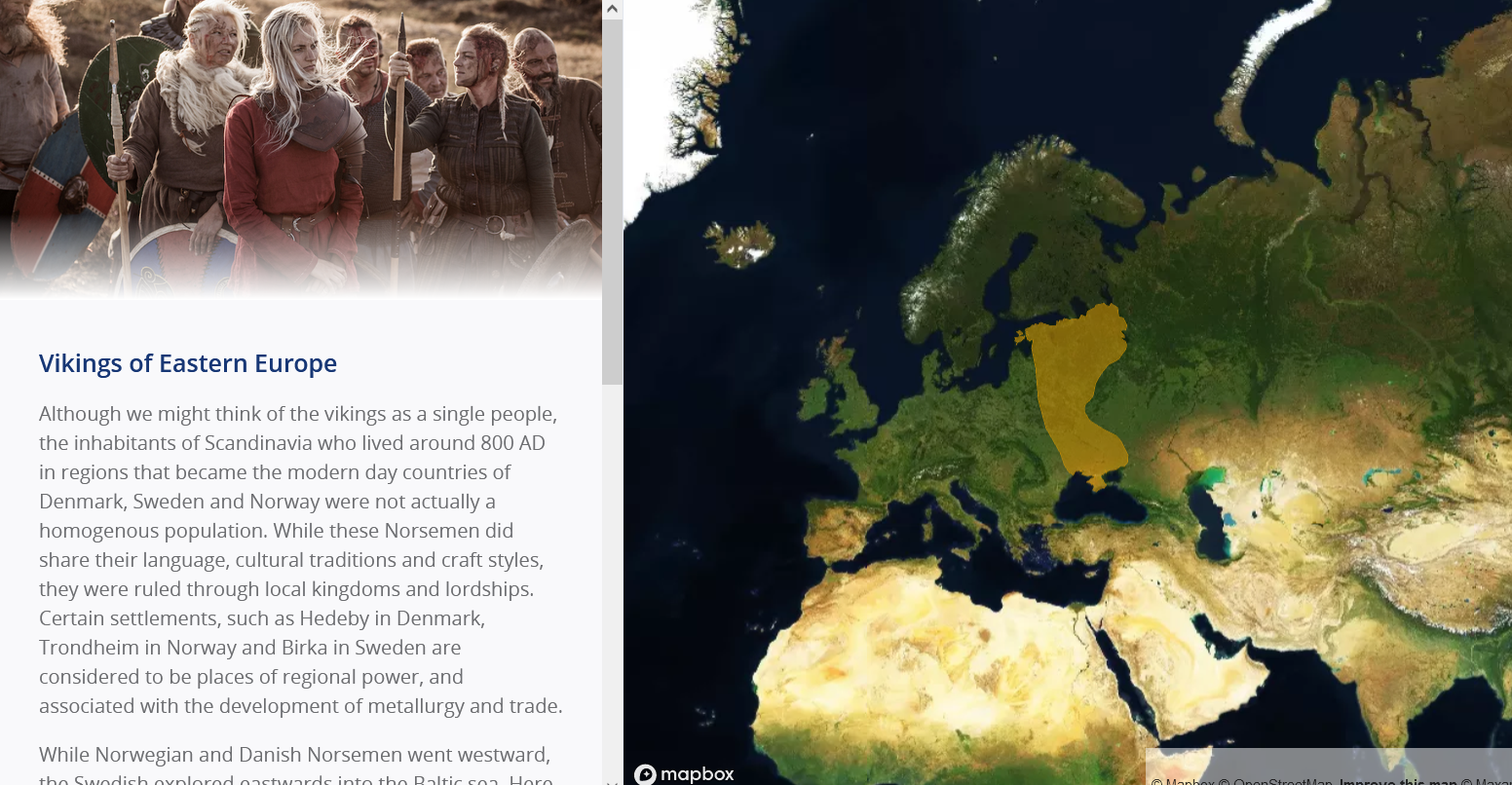

Vikings of Eastern Europe

Although we might think of the vikings as a single people, the inhabitants of Scandinavia who lived around 800 AD in regions that became the modern day countries of Denmark, Sweden and Norway were not actually a homogenous population. While these Norsemen did share their language, cultural traditions and craft styles, they were ruled through local kingdoms and lordships. Certain settlements, such as Hedeby in Denmark, Trondheim in Norway and Birka in Sweden are considered to be places of regional power, and associated with the development of metallurgy and trade.

While Norwegian and Danish Norsemen went westward, the Swedish explored eastwards into the Baltic sea. Here they found the estuaries of the rivers that lead inland across Eastern Europe into modern day Belarus, Russia and Ukraine, travelling along the Volga and Dnieper rivers until they reached the Black and Caspian Seas. On this journey these Vikings became known as «Rus» or «Varangians» by the Slavic people they encountered. Expanding partly through raiding, but mostly by trade, their influence grew. When they reached the Byzantine city of Constantinople on the Black Sea, it was raided in 860. In the aftermath of the raid, the Norsemen were accepted as trading partners by the Byzantines, an agreement which greatly increased the wealth and influence of the Varangians. The Varangians were here to stay.

In 862 Prince Rurik of the Varangians was invited to rule over the Slavic peoples to the south of the Baltic Sea. He founded his capital city of Norvgorod on the Volkhov river, and his descendant Oleg expanded their territory further into the south along the Dnieper river. Oleg eventually took control of Kiev in 882. It was from here that he decided to now rule, and continue to gain more territory. By 885 Oleg had united the majority of eastern slavic peoples under his rule and thus the country of Kievan Rus was born.